| date: | 2010 — 2012 |

| preliminary remark: | A selection of my Facebook posts and personal notes about maths. I was a funny mathematician — hilarious even — before becoming a visual artist! |

The difference between high school students and undergraduate/graduate maths students is that the former know what the cosecant of an angle means whereas the latter don’t.

So kids, don’t worry about your difficulty in trigonometry, I can assure you that ours is worse.

interview by Jason Polack

Long time ago I read a book chapter by Reviel Netz [1] attempting to draw a group portrait of Greek mathematicians (anyone who had written original demonstrations relating to maths) from classical times down to late antiquity. According to his estimation, there were about one thousand mathematicians in antiquity, making up less than 1% of the population. Despite the exponential growth of world population and the definition issue, the fact remains that mathematicians form a minority group in the modern time.

Given this disproportion, so little can be said by the majority of outsiders to characterise us in general, yet the silly caricature of eccentrically unsociable mathematicians has become the sole possible picture of our community in the public’s mind.

The more I am acquainted with other students, the more I can assure you, I am the only one who fits into that gross misrepresentation (the irony is that, professionally speaking, I am not a mathematician).

____________________

[1] Netz, R. (1999). The historical setting. In The Shaping of Deduction in Greek Mathematics: A Study in Cognitive History (Ideas in Context, pp. 271-312). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511543296.012

I saw a beardless logician today amongst a bunch of heavy-bearded logicians, and the reason for this shocking breach of the logician-stereotypic convention of beard-growing is: obviously enough, she was a woman.

A Christian who sees beauty in every creature, including monsters, is very intuitively sure that I have a beautiful soul.

I cannot deny I am flattered by this pretty compliment, but before a formal proof can be presented to me, my mathematical self enjoins me from believing this claim.

This statement made by a current grad student in the maths department deserves a permanent spot in the brains of those who have always wondered whether mathematicians consider themselves scientists:

I am not a scientist. I don’t do experiments. My job is to read books that I don’t understand and fall asleep.

Just awoken from a lethargic state of mind into which I had fallen while reading the combinatorics of Coxeter groups, I cannot find a better way to describe my vocation than by pointing to the above statement. Next time you should like to tell me the science of this or that, please recall that I am not a scientist; I am a mathematician.

Give me a mathematical definition of the concept of ‘fellowship’, and I will ask my probabilist colleagues to compute the likelihood of my experiencing such a thing within 5 years.

Those who don’t know that maths can be used to explain cultural preferences of rhythms in traditional music should take a look at these papers by Godfried Toussaint, a McGill professor who has uncovered the logic underlying the patterns of sounded events by applying computational geometry to the fields of mathematical ethnomusicology and music theory.

Next time if you see an absent-minded mathematician gazing at your feet while you dance, be not surprised, for she may be translating your footwork into undecipherable mathematical language in her uncanny head.

(Sorry folks, you have to admit one day, that maths can be done on the floor or on a keyboard, that musical rhythm and scale are proper objects of geometers’ contemplation, and that mathematicians are in charge of the world.)

[Linda] forgot to divorce from Maths to whom she was married a few years ago, therefore she remains today, as in the past, until discharged by due course of law, her Queen’s most humble and obedient servant. — Happy Pi Day.

Maths after mass… How devout must one who has been staying, barring a few hours of exception, in school since Thursday night, for the only object of translating her faith in mathematical truth into real-life action be (though with virtually no work done…)?

[Linda] prefers proofs, whenever proofs are possible.

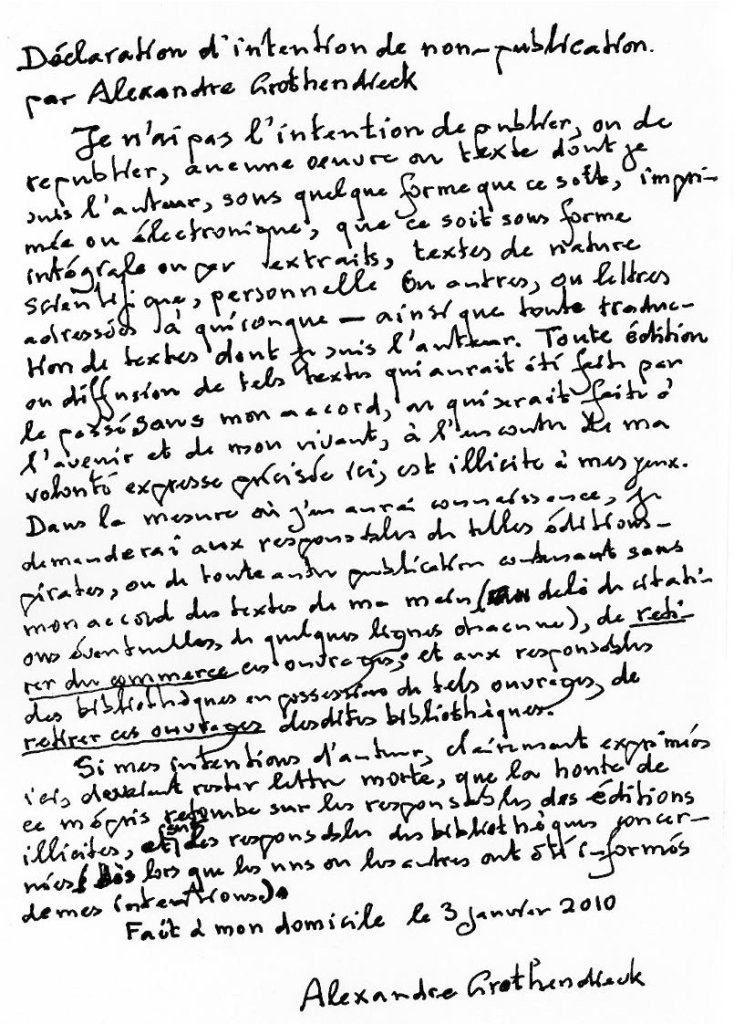

This is an event that may not be worth commemorating. One year ago, ex-mathematician Alexander Grothendieck, having sentenced himself to exile for life since 1991, shocked the world (of mathematicians, which I gather is fairly remote from the common life of common folks) with a hand-written letter expressing his disapproval of the unauthorised (re)publication of his earlier works, mostly accomplished before 1970. The authenticity of the letter, judging from the connexion with Luc Illusie, can be ascertained to a large extent, though doubt lingers still on why he had signed with ‘Alexandre’ instead of ‘Alexander’.

Although under extraordinary circumstances, an attempt to prohibit distribution of one’s discovery (as a kind of ‘intellectual property’ perchance?) on cyberspace to a wider mathematical community and for general mathematical use may be justifiable on rational ground, I fear that the career of younger researchers could be put at stake if there exists no measure to prevent such an endeavour that can create, whether purposely or not, a disincentive for further research, especially when the original works have transformative impacts on a discipline (impact is difficult to predict, to be sure). The mere thought that I would have to wait 50 years or so after Grothendieck’s death to release the old reliquary of his lofty opus into the sphere of public scrutiny again, were I to be involved in developing some body of mathematics directly built upon his works, makes me thankful that circumstances of my life had prohibited me from working, or planning on working, in the field of homological algebra or algebraic geometry.

In this case, can we say knowledge and mathematical discoveries are public properties, for which no one should hold the monopoly? Or can the plea for reissue of his works be made upon that he has been deprived of the status of the ‘legitimate rightholder’ since he has withdrawn from mathematical community for so long anyways? (I should add that the main cause of Grothendieck’s objection, if I err not, does not seem to be the copyright concern, but some other ethical concerns which I do not know very well.)

____________________

[1] https://sbseminar.wordpress.com/2010/02/09/grothendiecks-letter/

SBS is maintained by a number of recent Berkeley maths graduates, including Joel Kamnitzer who recently received a prize from CRM. There is a discussion thread on n-Category Cafe as well.

Ben Smith recently pointed to me Michael Atiyah’s extraordinarily difficult (*) paper ‘The Yang-Mills Equations over Riemann Surfaces’ (1983, joint with Raoul Bott), which had since 2009 baffled him for long. Its publication coincides so closely with Atiyah’s appointment as the president of the Mathematical Association from 1981 to 1982 [2] that immediately, I recalled a little essay of his, published in the journal of the association, in which Atiyah expounded his personal view on the nature of geometry: that, in summary, ‘geometry is not so much a branch of mathematics as a way of thinking that permeates all branches’.

Although speaking in favour of my subject-matter in a manner that is somewhat reminiscent of Jean Dieudonné who had promoted the ‘universal domination of geometry’ in a 1981 essay [3], Atiyah rather dampened in some measure the positive ardour in the mental complex determining my eventual emotional reactions to his point of view. For reasons that do not admit of rational elaboration (+), I was somehow struck by a nostalgic bewilderment concerning the means by which geometric ideas had been chosen for illustrative purpose, for a moment not knowing what kind of mathematician I intended to become. The area of mathematics bearing the name of ‘geometry’ had ramified in response to the changing needs of intellectual enterprises of humanity, into branches of nature so diverse that a geometer of antiquity, traditionally anchored in his/her own area of expertise, inevitably fail to follow the line of modern enquiry. Speaking for myself alone, I can hardly recognise the ‘geometric’ aspect of other sister disciplines; when flipping through a book on ‘moment polytopes’ another mathematical fellow who was making differential geometry his speciality showed me, I had a feeling that the entire treaty was written in Martian language, with esoteric jargon and indecipherable symbols.

That self-commiserating moaning aside, I learned recently that in a paper also published in 1982 [4], it was Atiyah who contributed the first development to the study of ‘moment polytopes’ resulting from the ‘moment map’ for a Hamiltonian action on symplectic manifolds: he showed the image of this map was a convex polytope. Now it becomes rather unthinkable — to me at any rate — that a mathematician of such scholarly excellence and intellectual maturity would later produced an article, ‘Polyhedra in Physics, Chemistry and Geometry’ (2003, co-written with Paul Sutcliffe) [5], to promote the idea that Neolithic carved stone balls discovered in Scotland constituted the full set of Platonic solids by using a photograph that unjustifiably pointed to some balls in the collection of Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. The idea was later popularised by several renowned, established mathematicians — John McKay and John Baez amongst others, and the same erroneous photo was used for a CRM conference — until Lieven Le Bruyn challenged this view in 2009 [6].

This Atiyah story may be getting too long for a casual and not fully digested comment; I shall stop after the last comment is made. Atiyah had written, as a member of the American Philosophical Society and Royal Society of Edinburg, prosaic-style essays on lofty topics that are closer to the realm of daily bread and domestic butter: science policy, philosophy of mathematics, history of Scottish Enlightenment, etc.

(*) The level of difficulty of the paper in question is proportional to the level of mental confusion and emotional distress currently experienced by our big Ben, still bravely unforsworn in his attempt to achieve a better understanding of the first few pages which amounted to a two-hour informal exposé given to an audience of 3 people this past Tuesday (what a perseverance!). Anyone who should itch to witness the human side of the esoteric world of mathematical research within which we receive our mental stimulus, is invited to Ben’s second exposé on the austere area of algebraic geometry on Thursday, 17 February 2011.

(+) Of my dejection I shall speak a few words later, lest my less favourable sentiment should be deemed contemptuous to the mathematicians for whom I do feel in many a way a very sincere admiration. Suffice it is to say for the moment that logic permeates all of mathematics, but is still considered a discipline in its own right.

____________________

[1] Atiyah, Michael. “What Is Geometry? The 1982 Presidential Address.” The Mathematical Gazette, vol. 66, no. 437, 1982, pp. 179–184. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3616542.

[2] The Mathematical Association came into existence for the original object of improving the teaching of geometry, now its scope has enlarged so as to encompass mathematical education in general. The list of past presidents can be found here: http://www.m-a.org.uk/jsp/index.jsp?lnk=831

[3] Dieudonne, J. “The Universal Domination of Geometry.” The Two-Year College Mathematics Journal, vol. 12, no. 4, 1981, pp. 227–231. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3027068.

[4] M.F. Atiyah, ‘Convexity and commuting Hamiltonians’, Bulletin of the London Mathematical Society. 14 (1) (1982) pp. 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1112/blms/14.1.1.

[5] M.F. Atiyah & P. Sutcliffe. ‘Polyhedra in Physics, Chemistry and Geometry’. Milan J. Math. 71:1 (2003) pp. 33–58, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00032-003-0014-1

[6] https://www.neverendingbooks.org/the-scottish-solids-hoax.html

Awakened to the hidden splendour of buildings, apartments, chambers, walls, stuttering galleries, Coxeter complex, Tits cone, W-metric space, Jordan-Holder permutation, twisted Chevalley group, Hopf algebra… Sometimes I do not know whether by dignifying abstract patterns of nature with so fanciful an appellation that charms the mind for a while, mathematicians are too rich in imagination or simply run out of words.

I am struggling to make my list of top 10 mathematicians, ranked according to my respective fondness for each of them. Nevertheless, there can be no doubt that Riemann is my #1, my Prince of all princes; had I not been acquainted with his mathematical legacy, I would not have fallen in love with Maths as a youngster (and I have remained in love ever since). Next comes my hero Coxeter, the King of Infinite Space.

Dear Bach, I need some of your spiritually uplifting music to recover my sanity after witnessing our all-too-busy maths grad students climbing walls, walking on the ceiling in our all-too-solemn mathematical sanctuary.

I have increasingly realised that part of my mathematical training consists in improving heart fitness to prevent sudden cardiac arrest that may occur at times unpredictable: after a nearly standing ovation concert, on the eve of final exams, on a Saturday night.

(A few days later, I uploaded the following photo)

My poor health had enjoined me making such strenuous physical effort. I was responsible for documenting others’ attempt at history-making.

(And this photo)

Mathematics is above all things the art and the science of the happy fews.

18 May 2010 (to a mathematician friend)

Your remark reminds me of this article I read earlier, on the gender disparity amongst high-achieving maths students in U.S. I dimly remember someone saying that the numbers of male and female math undergraduate students are not too far apart, yet significantly fewer female students pursue mathematics at graduate level. (In my search of a particular mathematician graduated from Princeton, I discovered by accident that, of a dozen newly admitted graduate students every year, at most 3 are female.)

It has been a century-old debate raging over the nature of human cognition and for want of a testable theory to explain the precise gene-environment interaction in the developing brain’s acquisition of what may be vaguely called abstract mathematical ability (what are the defining characteristics of this ability?), some will keep giving statistical analysis to boast, rather pompously, that biological difference accounts for the small minority of successful women in more cerebral disciplines, while others seek for empirical evidences in the rational defence of the opposite view and put primal emphasis on early learning environment. My ideal mathematician, self-sufficient and content in his/her natural state of mind, should not partake in such a debate that is of secondary importance to his/her vocation (G.H. Hardy would say it is the work for second-rate minds), for a genuine mathematician’s province is to develop new mathematical thoughts, not to justify the merit of his/her academic endeavour to the rest of mankind.

I for my own part have never experienced discrimination of any kind in school which some claim to be still present in American academia, never felt female scholar’s intellectual legacy being underrepresented (albeit some male contemporaries’ achievement might have been exaggerated to stupendous extent, but whether this can be qualified as a gender-related issue I am not too certain). The role of World Citizen may inflict more social responsibilities than what are necessary upon an individual involved in the pursuit of mathematical truth as a student, and I dare not aim at becoming a public intellectual ready to tackle on public policy.

18 May 2010 (to a mathematician)

My peculiar affinity with a quasi-Platonic reality prohibits me from accepting your contention. Everything irrelevant to the delightful study of mathematical objects is mere distraction that drives me away from the bright countenance of mathematical truth.

18 May 2010 (to unknown recipient)

Your character is quite contradicting. Contradiction is mathematician’s enemy.